Opening up architecture beyond sight

In this special podcast, Dr Jos Boys and Poppy Levison come together to discuss the barriers which blind and partially sighted people face in architectural education and practice – and how these can be overcome, for the benefit of everyone and the enrichment of the field. We hear in particular about the Architecture Beyond Sight project, developed by The Bartlett, UCL’s Faculty of the Built Environment, in collaboration with The DisOrdinary Architecture Project.

Dr Jos Boys is Co-Director of The DisOrdinary Architecture Project

Poppy Levison is a blind architect and a guest tutor for Architecture Beyond Sight

Further reading:

The DisOrdinary Architecture Project

Transcript:

Dr Jos Boys: Hi, I'm Dr Jos Boys. I'm co-director of the DisOrdinary Architecture Project, which I set up with disabled artist Zoe Partington in 2007/08. We've aimed to promote new models of practice for the built environment led by the creativity and experiences of disabled and D/deaf artists.

This podcast today is to talk about how architecture can be more inclusive of, and benefit from, blind and partially sighted students and practitioners. We're particularly talking about the Architecture Beyond Sight short course, which is a collaboration with The Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment at UCL, in particular with the B-made fabrication workshop that's part of The Bartlett School of Architecture.

Architecture Beyond Sight is a one-week intensive foundation programme for blind and visually impaired people who want to become architects. The intention has been to both support more disabled people into architectural education and practice, and to challenge conventional ways of teaching architecture that prioritise the visual over the other senses. Because of the pandemic, we've only been able to run this course for the second time in the summer of 2022, and we had 10 blind and partially sighted participants with the course being led by blind and partially sighted tutors Duncan Meerding, Zoe Partington and Mandy Redvers-Rowe. What I'd like to do is welcome Poppy. Perhaps Poppy, you'd like to introduce yourself.

Poppy Levinson: Hi, I'm Poppy Levison. I am blind, and I was a participant on the 2019 Architecture Beyond Sight course. I am since then doing my BA Architecture at Central Saint Martins. I'm currently doing my third year part-time and working as a Part 1 architectural assistant at DSDHA.

JB: And Poppy, although you were one of the original participants on the course, it's also true that post-pandemic, when we've not been able to run it, this summer we ran it again and you came back as a guest tutor in the workshop. So, can you tell us a little bit about your experience of the course and its impact on your work?

PL: Yeah, I think the impact of the course on both my perception of myself as a blind person and on my practice as an architect is… it's hard to sort of quantify how much it's made a difference. It was the first time that I'd properly spent time around a large group of other blind people and being taught by blind people and visually impaired people, which makes a huge difference.

Seeing people like me doing things and not having any issue with it and just making the best of it and being proud of being blind or visually impaired, just fundamentally changed the way I perceived myself and gave me this sort of self-confidence that is one of the things that has got me through architecture school, which can be notoriously difficult for anyone, let alone a blind person. But it also set me up with loads of really great practical skills. I was in a workshop, I was being taught by a blind person in a workshop and the support staff were all very supportive, which unfortunately isn't always the case. In workshops sometimes you can have experiences where – for health and safety reasons – people don't like blind people in workshops. But we can be there, and this course really showed me that.

And so because it's been such a big part of my life, it was so lovely to be able to come back and teach on it and see other people go through that same experience that I had, and also to just see how much I had progressed and how much I'd learned and developed since being able to take part in it.

A student at an Architecture Beyond Sight workshop. Photo: Viktoria Viktorija

A student at an Architecture Beyond Sight workshop. Photo: James Green

JB: Fantastic. And I do, I think to see a whole range of different blind people using power tools in the workshop, using band saws and equipment of that sort, and doing that in their own right without the technicians trying to stop you, just really felt such a positive and energising experience.

PL: And being actively encouraged by those technicians to do things and to push you out of your comfort zone is even better.

JB: Yeah. I mean, what's been interesting for me about the DisOrdinary Architecture Project over the years is that we've become increasingly aware, working in different architecture schools and practices, is that there are already many, many disabled people in architectural education and in the profession, mostly with invisible impairments, but also including lots of people, for example, who are partially sighted. But we've also found out that disclosing that impairment really works against the kind of educational and employment opportunities that different disabled people have. So I wondered if you could talk a little bit about some of the barriers you've experienced?

PL: The barriers have been very significant and it's easy when talking in situations like this to want to be like: “It's been great and I'm doing really well!” And the truth is, I am doing well now, but that doesn't mean that it hasn't been really hard and also that I haven't had to hide how hard it's been to a lot of people through the process.

I kind of felt like I didn't really have a choice but to disclose my disability. I thought starting an architecture course as a visually impaired person at the time, I needed the support more than I was scared of the negativity. I also felt fairly confident with my university, from what I'd experienced, that they would be supportive and that was part of my decision to go there. And also off the back of the course – I mean, the course was the summer before I started university – it gave me this sort of fire in my belly to go: you know what? I'm going to be here, I'm going to be in an art school campus, in an architecture department, every day with my white cane. And that gives me so much joy, even on some of the rough days when everyone is staring at me. You know, I also have to think all of those people that are staring at me are seeing a blind person in a space, and there's a lot of power in that.

But equally, I have had to fight things. I was definitely in a situation where, as well as doing the course, I was having to work out how I do the course as blind person and then having to fight to be able to do it that way. And that was taking days of my weeks away, which in a very tight schedule with architecture, really, I mean the biggest thing that meant my work suffered was the amount of time it took me to get my access needs met. It was never that I was incapable of doing the work. I mean, yes some of the work was difficult, but I wasn't incapable of it. I always understood everything, but I was having to fight so hard to get the help that I needed and am legally entitled to.

And that's one of the reasons that I have gone part-time on my degree, is that it meant that I had the time to do things properly and actually not have an incredibly stressful life, which unfortunately is what makes a lot of disabled people drop out of university in general is the amount of time it takes to get your access needs met.

JB: I think it's just, you know, those experiences are so common and they're still not being dealt with across the sector really – the higher education sector. I mean, one of the aims of Architecture Beyond Sight has been not just to have more blind and visually impaired and other disabled creative people in architecture and the built environment subjects. But also to challenge the kind of normativity of those subjects and how we might do them differently, how having a much more diverse group of people studying will affect what design methods we use, what curriculums we have, and how we can create a truly accessible environment. So thinking about Architecture Beyond Sight, can you talk a little bit about the kind of the things happening around non-visual design methods, for example?

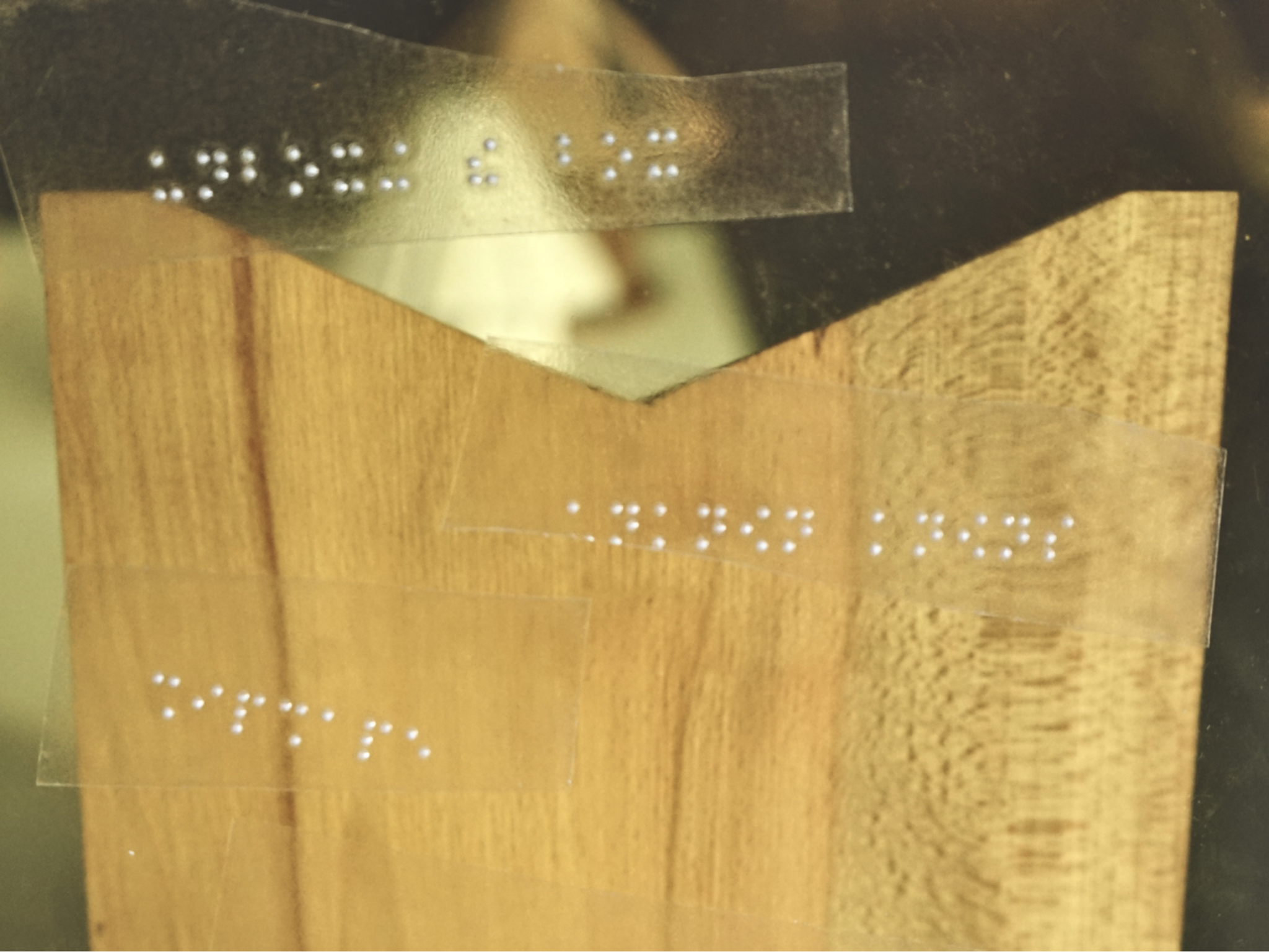

Detail of a model created at an Architecture Beyond Sight workshop. Photo: Viktoria Viktorija

There's this potential for so much richness that is currently underdeveloped

PL: That's really interesting, and I think that was also something that I got out of the course was that I'm very much in a situation, and I'm still in this situation, where I have to sort of pass as a sighted person. I have to do everything as a sighted person currently. And that is difficult because obviously I am not a sighted person. I have a little bit of sight left and so that makes things really hard. But what I think is so great about the course is it made me realise that there was a future in which I could do things completely differently and they would be great, and better, and stand in their own right. And so it's been great seeing those kind of non-visual methods of working and starting to think about how we could move towards an architecture that is less visual and a potential completely non-visual way of experiencing and practising architecture.

JB: Can you give some examples from the foundation course?

PL: What I find particularly interesting is the kind of spoken architecture. I think I've had experiences at university where I've been told by people that: “Oh, the more you're in architecture, the more you'll draw things rather than write about them.” As though the visual is king. And I think it's really sad because there is amazing writing about architecture, and yet it's not given the same sort of place within the profession. And I think something that would be really, really positive about having more blind and visually impaired people in architecture is this increased use of language. I really want to explore the kind of audio-described architecture, and that was something that people were practising on the course. And I think there's so much potential to discuss the other ways that we experience space through describing it. And it's a really great tool for architects to think, okay, how am I actually describing it? How would I describe this space? Do we even have the language to be able to describe these places properly? So I think there's this potential for so much richness there that is currently underdeveloped.

JB: Absolutely. And one of the things I really loved, and felt like as a sighted person that I really learned from and now use in my teaching a lot, is audio-describing spaces. That if you're sighted, actually you learn a lot by trying to audio-describe spaces. And also if you're working with blind and visually impaired people, you understand much more about the range of ways in which people understand space – and they're very expansive and beautiful ways of understanding space. So that together with the more performative aspects, where people would perform a space, and the different ways of modelling – sketch modelling in card or Lego or plasticine, or by sewing – that all those things, making tactile versions of, not necessarily tactile versions of plans, but using tactile methods for describing things, I think is just fantastic.

The next question is a little more general, and in a way it's not up to you to solve. But I wondered from your own experience, how do you think architectural education and practice need to improve, to be more inclusive and accessible?

Poppy Levison with a student at an Architecture Beyond Sight workshop. Photo: James Green

Students at an Architecture Beyond Sight workshop. Photo: Viktoria Viktorija

PL: I think a really easy one on this point is overwork – which obviously a lot of people are doing work about now, which is really great, and it's great to see the union shouting about this and Future Architects Front. But I think we need to in that process – and the union has been really good on this – start recognising the intersection with disability. You know, I'm at a place where the prospect of working full time is really daunting. I, as well as being blind, have chronic migraines associated with my vision loss and that is currently not compatible with full-time architecture employment, which is really full on. And I love my job and I love that it's pushing me all the time, but equally it's constantly a certain level of stress, and that's just assumed that that's just architecture now. Everyone just kind of goes: “Oh, well, we just do things in overtime, if you want to do anything different, you have to do it as a side hustle.” And that is inherently ableist.

There are so many people that can't work to those times. There are so many people that can't work to such fixed deadlines. And there’ll probably be a lot of non-disabled people listening, thinking: “Oh, that's just what disabled people are like.” But, it’s not working for you either. Like, there are so many architects leaving the profession, there are so many architects that aren't happy, are getting really burnt out. Like, this is not just a disability issue, but if we come at it from a disability perspective, it might really help the situation.

JB: Yeah. I mean, there's still such a model of being an architect or an architectural student, which is: you have to be obsessive, you have to work all hours, you're somehow unencumbered. You don't have a social life or a personal life.

PL: God forbid you have kids, you know?

JB: You don't have kids, you're not caring for other people. There's a kind of whole character type, a kind of ideal character type, that's really problematic for everybody. And I think for me, it's also problematic for the practice of architecture because it doesn't give you time to process, it doesn't give you time to reflect, doesn't give you time to research or read. I'm always being asked for a kind of instant solution to access. It's like: “Well tell us what to do, give us the template.” It's not: “Let’s actually think about different kinds of bodies and minds and how we occupy space as a very creative generator that we can build on.” It becomes just: “Give us the solution so we don't have to think about it because we don't have the time.” So I think that's a really important point.

We're just in the process of looking to develop a sister course to Architecture Beyond Sight for D/deaf and hard of hearing participants. And it has a very similar aims of bringing more creative disabled people into architecture, and again to challenge conventional approaches. And there's lots of really interesting concepts from D/deaf communities around D/deaf Gain, D/deaf space, which I think aren't well known in a kind of mainstream, normative architectural education and practice. So I'm expanding from that because I'm interested in what you think, what your advice might be for other disabled people who are interested in a career in architecture.

Students at an Architecture Beyond Sight workshop. Photo: Jos Boys

We need more and more diverse people in architecture

PL: I think the concepts of D/deaf space and D/deaf Gain are absolutely fascinating and I think they represent so much disability positivity. And I hope that something that might come from the Architecture Beyond Sight course is more of a blind identity when it comes to space, and also more people experiencing this sort of blind pride and being proud of being blind, which kind of goes hand in hand with D/deaf Gain for me.

And I think what I would say to people considering a career in architecture, it would be to try and find other disabled architects and people in architecture, because I know that that's what has made the biggest difference for me, is finding that community. And because of the current situation, we might all be very busy, but we will always give you the time of day and we will always give each other the time of day because we know that we will need it. And I think a lot of really great work is being done to try and establish these networks. And I think that is the way that you'll get through this, is finding other people and sharing knowledge.

I mean, it's taken me a year to actually finally getting contacted by a blind student that I've known about for a year but couldn't be put in touch with because of GDPR. And she's having to work out how to do all of the same things that I've had to spend weeks of my life working out how to do. And so it's currently a ridiculous situation where we're both having to work out how to do architecture as a blind person, and there's no knowledge sharing. Like, everything will be so much easier if we can share this sort of burden of access and share that work and share that knowledge and sometimes just have a rant to one another about the situation, or a disability adviser who just said something stupid, you know? So perhaps as difficult as it is, as advice for people, I mean, my advice would be go for it if it's what you're passionate about and find a community. Find the community.

JB: Thank you. And I think the big thing for both of us ultimately is that we need more and more diverse people in architecture, including diverse disabled people actually as creative practitioners, and we need to get to a kind of critical mass where it's just normal. And we're at the very early stages of that. It feels like it's something that's really important. Without it, the profession will continue not to be inclusive. And the way that we design spaces, the way we think about access will continue to be incredibly banal and really just not acceptable, I think.

PL: Yeah, I mean, the thing that gives me energy when I'm having to fight every tiny battle that I don't have the time or energy to fight, is this sort of hope that by me putting that energy in now it would be easier for the (even if it's just one) person that comes after me, so that they can fight the bigger battles and they can keep fighting. Yeah, I'm really hopeful that we'll get to a place where instead of people going: “How can you even do architecture as a blind person?!” They'll go: “Oh, you're blind. Okay.” It might take a while, but we'll get there.

JB: Yeah, and we'll all learn it. It'll improve the whole range of ways in which we design, in which we think about built space. Thank you so much, Poppy. Poppy Levison, thank you.

PL: Thank you.